The practice of human zoos, while largely associated with European colonialism in Africa, also inflicted unspeakable horrors on indigenous communities in the United States during the early 20th century. This chapter will examine the social, political, and historical context that led to the exploitation and humiliation of Filipino people in human zoo exhibits across America.

The United States signed a treaty with Spain in 1898 that ended the Spanish-American War, and as a result, acquired Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. The campaign for the Philippines was particularly brutal, resulting in the deaths of tens of thousands of Filipinos, and the infamous “Burgweed Report” estimated that up to 200,000 Filipinos died as a consequence of the war and subsequent American military rule. As part of this colonial expansion, the United States brought approximately 1,300 indigenous Filipinos to the United States in the early 1900s to be showcased in human zoos.

The human zoo phenomenon was not new in the United States, with slavery and segregation marking it as an extension of American history. Different ethnic and cultural minorities were dehumanized and displayed for entertainment. While viewing slaves and African Americans as wildlife eventually led to the abolitionist movement, American colonialism led to the exploitation of indigenous people in the United States and abroad.

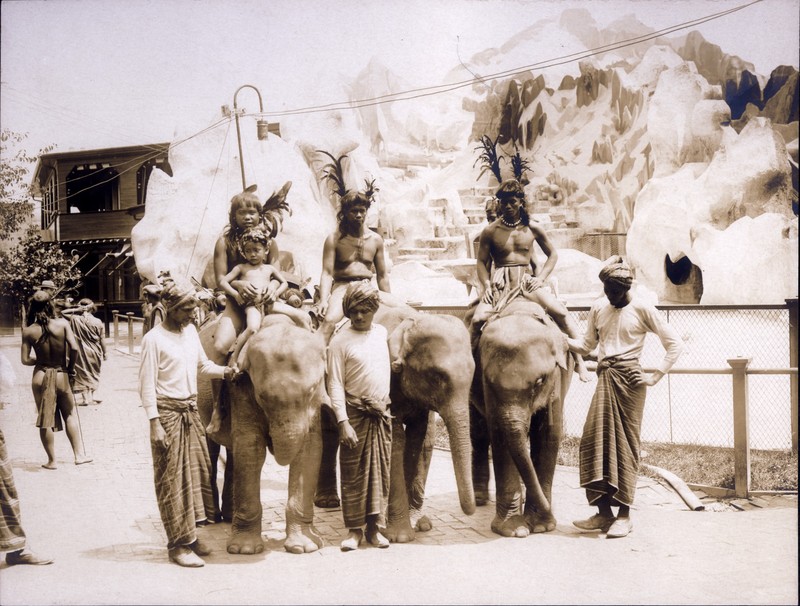

Filipino people were particularly attractive for these displays as they came from faraway colonies. The United States aimed to normalize American imperialist ambitions by presenting Filipinos as primitive and inferior, highlighting the virtues and progressiveness of American civilization. Filipino Zoo Girl, as we’ll call her, was torn away from her family and homeland and brought to America to fulfill this representation. Her captivity, as described by a visitor in St. Louis Exposition, was terrible. She was bound by ropes, unable to move freely, forced to stand in a small cage day after day surrounded by monkeys and lizards. Visitors would come and stare, some throwing peanuts at her as if she was just another animal in the zoo.

The human zoos found in America often duplicated the African traditions that saw black people held captive for the amusement and education of the public. A dispersion of indigenous people followed a familiar pattern in human zoos. They were classified into tribes, among them “Negritos,” “Ammorart,” “Aeta,” etc. The segregation and classification of these people served as a justification for American superiority and a reinforcement of the colonial dogma. Grass was spread within the cage to imitate jungle foliage, and mushy fruit was distributed to feed them, with the suggestion that they ate nothing else. Dressed in native garb, the indigenous were trained to perform their supposed traditional practices, portraying their cultures as woefully distinct from American civilization. The exhibits often utilized cages, chains, bars, and enclosures to imprison the “exotic” captives in an apparent imitation of the African cultures that involved the captivity of humans as trade slares.

These zoo exhibitions transformed into a valuable tool for American propaganda, which, by exporting American imperialism to other countries, helped shape the emerging dominant discourse of international relations. The political, social, and educational underpinnings of human zoos encapsulated a fundamental aspect of bourgeois sensibilities. The presentation of the indigenous was integral to the market economy, and they represented exotic goods to be sold for entertainment and education. The exhibition of cultural minorities as spectacles for the American public reflected Western imperialism’s espousal of superior academic and economic burdens. Human zoos were a manifestation of the connection between modernity and scientific progress as significant markers of profitability, social status, and political power that upheld the capitalist ideologies as global ideals.

The human zoos that were predominant in Europe traveled to the United States, encouraging colonial nations to present their nations in a similar light. This colonial effect engendered the emergence of television and radio shows that depicted foreign cultures as inferior, with magazines and newspapers continually pushing the continental divide. The portrayals of “primitive” indigenous folk became an accepted cultural belief pattern that reflected the colonial ideologies’ precepts, influencing how America dealt with immigrants and other ethnic minorities.

In contemporary America society, people tend to think of colonialism’s human zoos as the preserve of Europeans alone, unaware of their significance within American colonial history. The exhibitions remain taboo subjects, absent from most history books, resulting in a disavowal of America’s role in these inhuman actions. The lack of interest may arise from a general malaise regarding the United States’ treatment of indigenous communities, overlooked by many people. However, the concepts during human zoos remain part of American ideology, manifesting in how America and other countries perceive indigenous communities from America’s colonial past to today.

image sources

- Igorrotes_at_Hagenbeck’s: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Igorrotes_at_Hagenbeck%27s.jpg#/media/File:Igorrotes_at_Hagenbeck's.jpg